Greetings, Blog-pilgrim,

Most blogs are an ongoing flow of ideas and thoughts; this one had a very specific life-cycle, which has come to a close.

It was a summer writing project, from April through September of 2007, meant as a way to continue my learning process during the lull in classes for my masters in counseling psychology. I wrote about anything that popped to mind regarding my two favorite subjects: Culture and psychology. Sometimes they intertwined, sometimes they coursed along parallel river-beds, swelling and receding of their own accord. I was just the happy scribe in the bouncing kayak with a laptop on his knees.

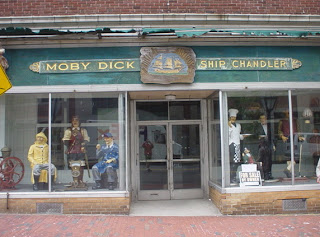

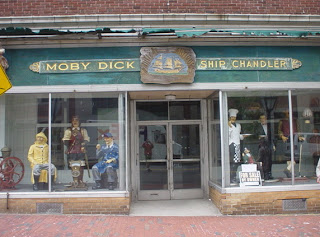

Within, you'll find reflections on my summer reading, from literary spoofs on Moby-Dick to cultural psychology takes on The Dangerous Book for Boys. You'll also find many posts about people with Asperger's syndrome, as I was working at a camp for children and teens with AS -- and loving the heck out it.

Feel free to roam around at will. Isn't that the joy of others' blogs?

Blessings on the journey.

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

Thursday, September 20, 2007

The Seven-Per-Cent-Solution: 100% Fun

This post is dedicated to Eric Little: Blogger, teacher, inspiration. Rest well, Eric.

This week, the beloved and I finally got to watch the film version of The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976), adapted from the book of the same name, reviewed here in Thinkulous.

I enjoyed the book very much, and the film did not disappoint. There were a few moments in which I inwardly winced because the script (written by Nicholas Meyer, who also wrote the novel) deviated quite a bit from the book. But these were minor plot points. Generally, he managed to be both faithful and successful, keeping the pace swift and entertaining.

Fine acting from Alan Arkin, as the 30-something Sigmund Freud in the period just before his breakthrough work in psychology and the unconscious. Arkin was just as natural and appealing as could be. Nicol Williamson was electrifying as a strung-out Holmes, throwing himself into the role. Perhaps just a titch over the top here and there, but generally, it only added to the general zest of the movie.

When I first read of the movie, I was stunned at the choice of Robert Duvall for Watson. He's a very fine actor, but, like most big-name American actors of his generation, most adept at playing himself, regardless of the role. I expected him to be the weak point in this film, and he was -- but not by far. He did a very serviceable job, and did not get in the way of people obviously more suited to their characters. He nicely embodied Watson's Victorian, bougoie restraint and propriety, as well as his unbridled affection for his notorious friend. His English accent was noticeably labored, but more than acceptable. In the end, I enjoyed his performance, though I can imagine two or three Brits who would have served the role quite a bit more admirably.

Kudos also to Lynn Redgrave, who plays the French victim of the fiendish plot Holmes and Freud manage to foil (I trust I'm not spoiling anything by sharing that little piece of info). Finally, Joel Grey made a wonderfully craven lackey for the Baron von Leimsdorf -- a respectable turn by Jeremy Kemp.

Good luck finding it -- the beloved is a librarian and was able to requisition a distant VHS copy. From what I hear, there has been no DVD release (this is criminal). But it is worth the search.

Thanks to Eric for his encouragement to seek out this film. He was a Williamson fan.

This week, the beloved and I finally got to watch the film version of The Seven-Per-Cent Solution (1976), adapted from the book of the same name, reviewed here in Thinkulous.

I enjoyed the book very much, and the film did not disappoint. There were a few moments in which I inwardly winced because the script (written by Nicholas Meyer, who also wrote the novel) deviated quite a bit from the book. But these were minor plot points. Generally, he managed to be both faithful and successful, keeping the pace swift and entertaining.

Fine acting from Alan Arkin, as the 30-something Sigmund Freud in the period just before his breakthrough work in psychology and the unconscious. Arkin was just as natural and appealing as could be. Nicol Williamson was electrifying as a strung-out Holmes, throwing himself into the role. Perhaps just a titch over the top here and there, but generally, it only added to the general zest of the movie.

When I first read of the movie, I was stunned at the choice of Robert Duvall for Watson. He's a very fine actor, but, like most big-name American actors of his generation, most adept at playing himself, regardless of the role. I expected him to be the weak point in this film, and he was -- but not by far. He did a very serviceable job, and did not get in the way of people obviously more suited to their characters. He nicely embodied Watson's Victorian, bougoie restraint and propriety, as well as his unbridled affection for his notorious friend. His English accent was noticeably labored, but more than acceptable. In the end, I enjoyed his performance, though I can imagine two or three Brits who would have served the role quite a bit more admirably.

Kudos also to Lynn Redgrave, who plays the French victim of the fiendish plot Holmes and Freud manage to foil (I trust I'm not spoiling anything by sharing that little piece of info). Finally, Joel Grey made a wonderfully craven lackey for the Baron von Leimsdorf -- a respectable turn by Jeremy Kemp.

Good luck finding it -- the beloved is a librarian and was able to requisition a distant VHS copy. From what I hear, there has been no DVD release (this is criminal). But it is worth the search.

Thanks to Eric for his encouragement to seek out this film. He was a Williamson fan.

Wednesday, September 19, 2007

Autism and Masculinity

Very interesting article on the BBC Web site last week, about research into high levels of testosterone in fetuses that would later become children with autistic traits.

Eight years of research show a fairly high correlation (20% in the world of scientific research is very high indeed). However, it’s just a beginning: The link is only to autistic traits, not the disorder itself, and there is no way to know at this stage whether testosterone causes the traits, or is just correlated for any of a number of possible reasons.

This furthers the interesting hypothesis of the well-known British autism expert, Simon Baron-Cohen (no relation to Sasha) that symptoms of the disorder, such as highly analytic and logical thinking, social isolation, and others, are an expression of male thought patterns in extreme, unhealthy form. He thinks that perhaps the testosterone creates a brain in which this is inevitable. More specifically, Baron-Cohen says...

Eight years of research show a fairly high correlation (20% in the world of scientific research is very high indeed). However, it’s just a beginning: The link is only to autistic traits, not the disorder itself, and there is no way to know at this stage whether testosterone causes the traits, or is just correlated for any of a number of possible reasons.

This furthers the interesting hypothesis of the well-known British autism expert, Simon Baron-Cohen (no relation to Sasha) that symptoms of the disorder, such as highly analytic and logical thinking, social isolation, and others, are an expression of male thought patterns in extreme, unhealthy form. He thinks that perhaps the testosterone creates a brain in which this is inevitable. More specifically, Baron-Cohen says...

… the hormone [testosterone] could be affecting the brain through altering neural cell connectivity and chemicals that carry messages, known as neurotransmitters.

The team is now planning to follow up its study to test direct links between autism and testosterone levels in foetuses. The group will use Denmark's archive of 90,000 amniocentesis samples and its register of psychiatric diagnoses.

The work is connected to Professor Baron-Cohen's hypothesis suggesting that autism is a version of the extreme male brain.

He said that although researchers had tested this theory at the psychological level, the new studies meant it could now be tested at the biological level.

Monday, September 10, 2007

Yawning and Autism

An interesting little insight into the minds of autistic children: They aren't susceptible to "contagious" yawns the way neurotypical folk are. Go to this page on one of my favorite blogs, Mind Hacks, to read the summary of an article in the journal of the British Psychological Society, and to get links to the original article.

Sunday, September 9, 2007

Gold Beats the Devil

I'm reviewing my pleasure-reading for the last few months (all documented extensively here on Thinkulous; just use the search field above if you want to read more on any of these books) and there is an undeniable theme emerging:

1) Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville: A rollicking story of a man's life-defining adventure, written in highly stylish prose, with historical and philosophical underpinnings.

2) Yiddish Policemen's Union, by Michael Chabon: A rollicking story of a man's life-defining adventure, written in highly stylish prose, with historical and philosophical underpinnings.

3) The Egyptologist, by Arthur Phillips: A rollicking story of two men's life-defining adventures, written in highly stylish prose, with historical and philosophical underpinnings.

Ah, but then there's my latest read, picked up this week while on a brief vacation on Cape Cod: Carter Beats the Devil, by Glen David Gold. It's an entirely different deal -- a truly rollicking... story... of a man.... hmm.

Charles Carter is an Edwardian-era prestidigitator, a card-and-coin man rising through the ranks of the vaudeville and chautauqua circuits. He spends his days in malodorous, musty train cars, dreaming of being a big-time illusionist like Mysterioso, who has an opulent train of his own and a secure spot at the top of the bill every night. Even before this endearing biographical adventure gets underway, Gold foreshadows the greatness in the offing, by way of an "Overture" in which Carter performs in a fantastically ornate theater in San Francisco, and receives President Warren G. Harding as a distinguished guest. I won't spoil anything here.

So far, it's a lovely vacation read. I commend Gold for not attempting overly flashy language; as I've pointed out here in posts on The Egyptologist, that seems to be the most common trap of the middlebrow novelist (a title I apply endearingly, by the way). Gold's prose is quite readable, and, at times, even flows admirably in its unpretentious portrayal of a very pretentious time and profession.

I'm only a fifth of the way in. So far, there's been a wonderfully brisk and engaging exposition, followed by some regrettable pages in which the language and plotting loses some of that crystal clarity. Am I one of the few people who have little patience for sweeping novels that bog down in day-to-day soap operas? There are so many of them. Even my main man Chabon is guilty at times (though rarely).

But I suspect I'm in for the long haul with Gold; I'm having fun. I'll keep you posted.

1) Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville: A rollicking story of a man's life-defining adventure, written in highly stylish prose, with historical and philosophical underpinnings.

2) Yiddish Policemen's Union, by Michael Chabon: A rollicking story of a man's life-defining adventure, written in highly stylish prose, with historical and philosophical underpinnings.

3) The Egyptologist, by Arthur Phillips: A rollicking story of two men's life-defining adventures, written in highly stylish prose, with historical and philosophical underpinnings.

Ah, but then there's my latest read, picked up this week while on a brief vacation on Cape Cod: Carter Beats the Devil, by Glen David Gold. It's an entirely different deal -- a truly rollicking... story... of a man.... hmm.

Charles Carter is an Edwardian-era prestidigitator, a card-and-coin man rising through the ranks of the vaudeville and chautauqua circuits. He spends his days in malodorous, musty train cars, dreaming of being a big-time illusionist like Mysterioso, who has an opulent train of his own and a secure spot at the top of the bill every night. Even before this endearing biographical adventure gets underway, Gold foreshadows the greatness in the offing, by way of an "Overture" in which Carter performs in a fantastically ornate theater in San Francisco, and receives President Warren G. Harding as a distinguished guest. I won't spoil anything here.

So far, it's a lovely vacation read. I commend Gold for not attempting overly flashy language; as I've pointed out here in posts on The Egyptologist, that seems to be the most common trap of the middlebrow novelist (a title I apply endearingly, by the way). Gold's prose is quite readable, and, at times, even flows admirably in its unpretentious portrayal of a very pretentious time and profession.

I'm only a fifth of the way in. So far, there's been a wonderfully brisk and engaging exposition, followed by some regrettable pages in which the language and plotting loses some of that crystal clarity. Am I one of the few people who have little patience for sweeping novels that bog down in day-to-day soap operas? There are so many of them. Even my main man Chabon is guilty at times (though rarely).

But I suspect I'm in for the long haul with Gold; I'm having fun. I'll keep you posted.

Sunday, August 26, 2007

The Egyptologist: Final Report

The Egyptologist turned out to be a good book, not quite delivering on its early promise, but definitely a rewarding read: fun and thought-provoking. At the very least, you'll learn tons about the sate of the art of archaeology in 1922.

The tedium in the second half, which I reported in my most recent post here, was relieved toward the end, when events finally began to break, a new character's perspective was added to the story (via yet more letters), and, of course, I finally found out who was who, and who done what.

"Who was who?" was really the more interesting question. The blurbs on the back of the book, by such luminaries as Gary Shteyngart and XXX, all call attention to the themes of immortality and fame in the book -- the most obvious topics Phillips was exploring, with everyone from pharoahs to academics to small-fry private eyes vying to burn their names indelibly into the pages of time. Indeed, Phillips has a very sure hand when painting people's vanities. Funny stuff.

But I was more intrigued by Phillips' games with the notion of identity. No one is who they seem to be, even after you think you've figured out who they really are. More interesting yet is who they think they are, and what they do because of it. The stories we tell ourselves about our lives, as any narrative-oriented therapist will tell you, motivate or justify our actions, and help us make sense of our past. When that capacity runs out of control, feeding and being fed purely by ego, how far out of joint are the results likely to be? Lives get their circuits crossed, and much disaster -- or hilarity, depending on how mordant your sense of humor is -- ensues.

The tedium in the second half, which I reported in my most recent post here, was relieved toward the end, when events finally began to break, a new character's perspective was added to the story (via yet more letters), and, of course, I finally found out who was who, and who done what.

"Who was who?" was really the more interesting question. The blurbs on the back of the book, by such luminaries as Gary Shteyngart and XXX, all call attention to the themes of immortality and fame in the book -- the most obvious topics Phillips was exploring, with everyone from pharoahs to academics to small-fry private eyes vying to burn their names indelibly into the pages of time. Indeed, Phillips has a very sure hand when painting people's vanities. Funny stuff.

But I was more intrigued by Phillips' games with the notion of identity. No one is who they seem to be, even after you think you've figured out who they really are. More interesting yet is who they think they are, and what they do because of it. The stories we tell ourselves about our lives, as any narrative-oriented therapist will tell you, motivate or justify our actions, and help us make sense of our past. When that capacity runs out of control, feeding and being fed purely by ego, how far out of joint are the results likely to be? Lives get their circuits crossed, and much disaster -- or hilarity, depending on how mordant your sense of humor is -- ensues.

Labels:

archaeology,

Arthur Phillips,

Egyptologist,

identity,

immortality,

plot,

review

Thursday, August 23, 2007

The Expedition Bogs Down

I've been enjoying The Egyptologist (see previous post) by Arthur Phillips, but I have to admit the second half hasn't been as fun as the first. He got off to a rip-roaring start, then settled in to pleasant clip. But by the mid-point, it began to feel like the Pulitzer Syndrome (see my explanatory post here) was setting in, even though his first effort didn't win that prize. It was, however, a huge success, and perhaps no one doing the preliminary reading for the second book had the guts to say, "Uh, listen Art, this is great stuff -- GREAT! But, uh... the second half; it gets a little, uh, slow."

Don't get me wrong, it's still quite enjoyable, and I might still recommend the book (I have to finish it to be sure). The characters are gorgeously drawn, and their language (on display so resplendently in their correspondence, which makes up the whole of the book) is delicious. But I feel like I'm stuck in the exposition section of the book and it's regenerating itself. Perhaps it's the device of using only letters as text that bound him to unfold the plot so slowly; each of the letter-writers doesn't know what the other one knows, and they're on opposite sides of the earth, in the 1920s, before international telephone service, much less email. It's amusing to watch letters cross in the mail, cables (enigmatically brief because of their cost) misinterpreted... but it can only provide the backbone of a story for so long.

Some of the characters might be utter liars, not even who they pretend to be. Some might simply be fooling themselves and wreaking havoc because of it. I'm tired, though, of not knowing and being pulled back and forth. It's unfair after 200 pages to not have revealed even a little of what's what. It's really quite fun for a good while, but then suddenly I find myself skimming whole paragraphs, even pages.

In the final third of the book,Trillipush interprets a very long set of hieroglyphs (not hieroglyphics, as he points out), and the resulting text goes on for pages and pages, doing nothing to move the plot forward. Oh, I get the idea: Phillips is doing a little reverse psychoanalysis, in which Trillipush uses the mytho-historical figure of the Egpytian king to vent all his inner frustrations and secrets. Clever and fun for a few paragraphs, but nothing new gets revealed. A little of this goes a very long way.

What keeps me reading is, of course, the desire to see the mystery solved. With all the excess, there's still a pull to find out whodunit, or, more aptly, who's fooling who. Also, there's still some good flavor left in Phillips' frothy concoction, even after pouring on too much sugar for too long. But he'd better move it along. His character Trillipush wowed his creditors into investing in his expedition with promises of a huge discovery of gold artifacts and historical insight. Phillips made a similar promise with considerable brio at the beginning of The Egyptologist. By now, both creditors and reader are getting impatient.

Don't get me wrong, it's still quite enjoyable, and I might still recommend the book (I have to finish it to be sure). The characters are gorgeously drawn, and their language (on display so resplendently in their correspondence, which makes up the whole of the book) is delicious. But I feel like I'm stuck in the exposition section of the book and it's regenerating itself. Perhaps it's the device of using only letters as text that bound him to unfold the plot so slowly; each of the letter-writers doesn't know what the other one knows, and they're on opposite sides of the earth, in the 1920s, before international telephone service, much less email. It's amusing to watch letters cross in the mail, cables (enigmatically brief because of their cost) misinterpreted... but it can only provide the backbone of a story for so long.

Some of the characters might be utter liars, not even who they pretend to be. Some might simply be fooling themselves and wreaking havoc because of it. I'm tired, though, of not knowing and being pulled back and forth. It's unfair after 200 pages to not have revealed even a little of what's what. It's really quite fun for a good while, but then suddenly I find myself skimming whole paragraphs, even pages.

In the final third of the book,Trillipush interprets a very long set of hieroglyphs (not hieroglyphics, as he points out), and the resulting text goes on for pages and pages, doing nothing to move the plot forward. Oh, I get the idea: Phillips is doing a little reverse psychoanalysis, in which Trillipush uses the mytho-historical figure of the Egpytian king to vent all his inner frustrations and secrets. Clever and fun for a few paragraphs, but nothing new gets revealed. A little of this goes a very long way.

What keeps me reading is, of course, the desire to see the mystery solved. With all the excess, there's still a pull to find out whodunit, or, more aptly, who's fooling who. Also, there's still some good flavor left in Phillips' frothy concoction, even after pouring on too much sugar for too long. But he'd better move it along. His character Trillipush wowed his creditors into investing in his expedition with promises of a huge discovery of gold artifacts and historical insight. Phillips made a similar promise with considerable brio at the beginning of The Egyptologist. By now, both creditors and reader are getting impatient.

Labels:

Arthur Phillips,

Egyptologist,

plot device,

Pulitzer

Tuesday, August 21, 2007

A Dangerous Plot for Boys

Greetings, friends. I feel the need to hail you because it's been so long between posts; days at a time. Life is a whirlwind here in Thinkuland.

Charles McGrath has an interesting article in last Sunday's Times about The Dangerous Book for Boys. (See my post on the book here.) It seems Disney has contracted with director Scott Rudin ("The Queen" and "School of Rock") to produce a movie based on the book. Hard to conceive, really. I liked the book, myself, but come on: A Rudyard Kipling poem and a piece on how to make a paper water-bomb hardly seem like blockbuster material.

McGrath points out that the book's not nearly as dangerous as it makes itself out to be, since "there is less stuff to do in [it] than to read about." True, though making a vinegar-powered battery might be as dangerous as we can hope for from today's plugged-in, tuned-out lads. (I spent the summer with 50 of them, and getting them to put their GameBoys away for more than five minutes -- even in favor of interpersonal games they really loved -- was a continual struggle.) And besides, dangerous or not, a vinegar battery is still pretty darn cool.

But like McGrath, I'm skeptical of the movie, and I enjoyed the plot line he predicts:

Charles McGrath has an interesting article in last Sunday's Times about The Dangerous Book for Boys. (See my post on the book here.) It seems Disney has contracted with director Scott Rudin ("The Queen" and "School of Rock") to produce a movie based on the book. Hard to conceive, really. I liked the book, myself, but come on: A Rudyard Kipling poem and a piece on how to make a paper water-bomb hardly seem like blockbuster material.

McGrath points out that the book's not nearly as dangerous as it makes itself out to be, since "there is less stuff to do in [it] than to read about." True, though making a vinegar-powered battery might be as dangerous as we can hope for from today's plugged-in, tuned-out lads. (I spent the summer with 50 of them, and getting them to put their GameBoys away for more than five minutes -- even in favor of interpersonal games they really loved -- was a continual struggle.) And besides, dangerous or not, a vinegar battery is still pretty darn cool.

But like McGrath, I'm skeptical of the movie, and I enjoyed the plot line he predicts:

A dad who, worried that his son is becoming a softy and a wuss, buys an under-the-counter copy of a mysterious Edwardian tome and forces the boy to listen as he reads aloud from it. “Don’t swagger,” he says, quoting Sir Frederick Treves. “The boy who swaggers — like the man who swaggers — has little else that he can do. He is a cheap-Jack crying his own paltry wares.”

Pretty soon the two of them are off in the woods together, killing rabbits, talking Latin, reciting Kipling and, safely away from women, companionably breaking wind. Junior ties knots, makes flint arrowheads and recites the rules of Rugby while Dad — Pater, that is — sucks on his pipe and lectures the lad about cold showers and avoiding “beastliness.”

Meanwhile, Mom has bought a book of her own, a home-repair manual, and has set about changing all the locks.

Friday, August 17, 2007

My Latest Read

Well, Friends and Romans, with my intense summer job over, my attention has finally been turning to other things. What with all the personal changes in my life creating a tsunami of a to-do list, I headed to the beautiful local library the other day looking to walk away with a fun, engrossing read, to substitute for the vacation I need. (Said library being a descendant of the first free children's library in the U.S., no less.)

On the way out of the house, I grabbed a worn scrap of paper on which, months ago, I’d scrawled the name of a book and its author. Somehow, it had survived the blizzard of papers crossing my desk in the intervening time. While I had no memory of who had recommended the book or why I thought it worthy of remembering, I usually have the devil’s own time finding a book I want to read (for reasons too lengthy to go into here, though perhaps I’ll post on this later and invite some suggestions.) So, I thought I’d look it up. What did I have to lose?

Now, I’m sure that, after that interminable introduction, you’re one step ahead of me, sweet reader, and are waiting for me to reveal the name of a book which, with barely a hitch in my step, I plucked from the burgeoning stacks of my local lending establishment, checked out with beads of anticipatory sweat dotting my fevered brow, and which I have been reading ever since, clawing my own shirt with pleasure at the astonishing plot twists and sparkling turns of phrase. That’s why I write this dotty blog in the first place, you see, is for people like you – yes, you -- who (heaven help you) think like I do, who keep me on my toes, who reward my humble, over-wrought efforts at cleverness with embarrassing heaps of indifference.

Well, now, if that’s what you’re thinking (about the book, that is), then, ha! That’s where I’ve got you.

Well, okay. Actually, you’re right.

If you’re looking for a bracing read, a ripping yarn, a wicked sense of humor, writing with the kind of style that’s just plain gone out of style in the last 30 years (with one or two shining exceptions), then, gentle subscriber -- oh, fair and loyal verbophile! -- make sure you read The Egyptologist, by Arthur Phillips.

(Talk about burying the lead.)

I guess it was the hot ticket a few years ago (published in ’04, it was), and, in fact, was Phillips’ sophomore jaunt, after the best-selling Prague, which you can bet your sweet little cell phone/PDA/text messaging/push-email-reader I’m going to check out next.

It’s clever and entertaining. It reveals the many (too many) secrets of its labyrinthine plot via two separate sets of letters, sent to two different people, 30 years apart. This device gives Phillips the chance to take his stylistic chops out on the open highway and unwind the engine to about 124 mph, because the two correspondents write very differently. Which is the kind of thing that could drive me batty and lead me to heave the book through a closed window, if Phillips were any less talented. As it is, I love the approach.

The only other author who pulls off this kind of dangerous nonsense with such verve and panache is my primary contemporary literary luminary: one Michael Chabon, my main man, my Karl Rove, the clean-up power hitter in my library line-up, who, even when he goes wrong, can do no wrong in my eyes. (Like most, I didn’t love Summerland, but didn’t I finish all 500-plus pages, now, and draw out the scarce drops of nectar from that half-wilted flower?)

Phillips – so far, and the chunk I’ve read so far seems fairly predictive – is no Chabon, though he clearly is aiming his Taw marble into the same artistic chalk-circle. He’s very good, and that’s saying a lot. But a very good cyclist can either choose a fairly off-beat event and work towards ruling it, or he can enter the Tour de France. If he does the latter, he just has to know up front that he’s going to lose every time to Lance Armstrong.

Coming in second in the Tour rocks pretty dang hard – and so does Phillips. So far. I’ll keep you posted.

On the way out of the house, I grabbed a worn scrap of paper on which, months ago, I’d scrawled the name of a book and its author. Somehow, it had survived the blizzard of papers crossing my desk in the intervening time. While I had no memory of who had recommended the book or why I thought it worthy of remembering, I usually have the devil’s own time finding a book I want to read (for reasons too lengthy to go into here, though perhaps I’ll post on this later and invite some suggestions.) So, I thought I’d look it up. What did I have to lose?

Now, I’m sure that, after that interminable introduction, you’re one step ahead of me, sweet reader, and are waiting for me to reveal the name of a book which, with barely a hitch in my step, I plucked from the burgeoning stacks of my local lending establishment, checked out with beads of anticipatory sweat dotting my fevered brow, and which I have been reading ever since, clawing my own shirt with pleasure at the astonishing plot twists and sparkling turns of phrase. That’s why I write this dotty blog in the first place, you see, is for people like you – yes, you -- who (heaven help you) think like I do, who keep me on my toes, who reward my humble, over-wrought efforts at cleverness with embarrassing heaps of indifference.

Well, now, if that’s what you’re thinking (about the book, that is), then, ha! That’s where I’ve got you.

Well, okay. Actually, you’re right.

If you’re looking for a bracing read, a ripping yarn, a wicked sense of humor, writing with the kind of style that’s just plain gone out of style in the last 30 years (with one or two shining exceptions), then, gentle subscriber -- oh, fair and loyal verbophile! -- make sure you read The Egyptologist, by Arthur Phillips.

(Talk about burying the lead.)

I guess it was the hot ticket a few years ago (published in ’04, it was), and, in fact, was Phillips’ sophomore jaunt, after the best-selling Prague, which you can bet your sweet little cell phone/PDA/text messaging/push-email-reader I’m going to check out next.

It’s clever and entertaining. It reveals the many (too many) secrets of its labyrinthine plot via two separate sets of letters, sent to two different people, 30 years apart. This device gives Phillips the chance to take his stylistic chops out on the open highway and unwind the engine to about 124 mph, because the two correspondents write very differently. Which is the kind of thing that could drive me batty and lead me to heave the book through a closed window, if Phillips were any less talented. As it is, I love the approach.

The only other author who pulls off this kind of dangerous nonsense with such verve and panache is my primary contemporary literary luminary: one Michael Chabon, my main man, my Karl Rove, the clean-up power hitter in my library line-up, who, even when he goes wrong, can do no wrong in my eyes. (Like most, I didn’t love Summerland, but didn’t I finish all 500-plus pages, now, and draw out the scarce drops of nectar from that half-wilted flower?)

Phillips – so far, and the chunk I’ve read so far seems fairly predictive – is no Chabon, though he clearly is aiming his Taw marble into the same artistic chalk-circle. He’s very good, and that’s saying a lot. But a very good cyclist can either choose a fairly off-beat event and work towards ruling it, or he can enter the Tour de France. If he does the latter, he just has to know up front that he’s going to lose every time to Lance Armstrong.

Coming in second in the Tour rocks pretty dang hard – and so does Phillips. So far. I’ll keep you posted.

Tuesday, August 14, 2007

Carl Rogers Pumps his Fist

Interesting article in the New York Times Magazine this past Sunday by Laurie Abraham: Can This Marriage be Saved? Abraham followed a couples therapy group for one year, and provides an insider view on both the interactions between the participants, and the therapist's thought process. I liked the thoughts and personality of the therapist very much -- she's well-educated, but at her best when she lets her instincts guide her and her quirky personality shine through. I find the same approach works for me, but I haven't had her years of experience to prove that it's safe (and more effective) to go that way. Reading about experienced clinicians at work is often helpful.

There are a few interesting segués in the article, and I wanted to call out one regarding what the literature has to say on the nature of an effective therapeutic relationship:

The second point seems to me simply to take point number one a giant step further. It may be stated just a little too loosely for my taste, but the gist, again, feels right to me. And while I can hear my more scientifically-oriented friends in the field (and the HMOs, and their panels of well-paid MDs) groaning loudly in the background as I type this, there is a boat-load of truth in this quote.

Thinkulous readers know that I'm a big fan of what science can tell us about our minds, emotions, and behavioral patterns. Neurological breakthroughs in the last 20 years have taken our understanding giant steps forward. Social scientists blaze wide swaths of fascinating new information, cutting through the vast forest of ignorance about our inner workings. I adore reading this stuff, and I try to integrate it into how I approach the field.

At the same time, I've always believed that science, art and mystery are not only highly compatible (in this and any field) but are actually three parts of one whole. What I know, and what I've yet to know that I know, flow together indistinguishably and create my unique approach to clients and clinical situations -- the art. Heck, they create me. And while I adore what science can add to that picture, there isn't an argument in the universe that will convince me that science is any more important than mystery, intuition and subjectivity. We're talking about the mind, about emotions, about self-hood. If it isn't subjective, we are, by definition, off track. How could we possibly quantify why certain people are healing to be around?

One well-recognized marker of mental health is flexible thinking. Practitioners spend a lot of time fostering in our clients a balance of healthy empiricism and risk-tolerant acceptance of the unknown. If the field of psychology doesn't admit pretty soon that the dynamics of pscyhological healing are at least somewhat unquantifiable -- while also unmistakable -- are we then practicing what we preach?

There are a few interesting segués in the article, and I wanted to call out one regarding what the literature has to say on the nature of an effective therapeutic relationship:

Investigators have repeatedly tried to single out specific "therapeutic factors" that can distinguish good therapy from bad, and the only unequivocal winner is what's termed a "positive therapeutic alliance," meaning the client feels that the therapist exhibits qualities like empathy and support.In school, I've had the point in the first paragraph drilled into me so many times I can't count. It's one of the foundations of the humanistic approach that Carl Rogers, a founding father of modern psychology, first defined. And it feels right on to me. (Note that there is a silly, 40-year-old myth related to this which holds that therapists are simply trained to either a) say back to you what you've said to them, or b) gush vague, unexamined supportive statements. Neither is true of a good therapist, regardless of his or her theoretical background.)

Jay Efran, a psychologist and emeritus professor at Temple University who surveyed the last 25 years worth of trends in therapy in an ambitious recent article (...) has another idea about what makes for an estimable therapist. He suggests that therapy boils down to a facility for conversation and therefore is a creative and contingent act that does not lend itself to formulas. "The profession has gotten itself into a bind," he told me recently, "because it wants to be seen as a science and it wants to collect money and it has made this category mistake of thinking it provides treatments for diseases and not just conversation or community or human contact or offering new slants on life."

The second point seems to me simply to take point number one a giant step further. It may be stated just a little too loosely for my taste, but the gist, again, feels right to me. And while I can hear my more scientifically-oriented friends in the field (and the HMOs, and their panels of well-paid MDs) groaning loudly in the background as I type this, there is a boat-load of truth in this quote.

Thinkulous readers know that I'm a big fan of what science can tell us about our minds, emotions, and behavioral patterns. Neurological breakthroughs in the last 20 years have taken our understanding giant steps forward. Social scientists blaze wide swaths of fascinating new information, cutting through the vast forest of ignorance about our inner workings. I adore reading this stuff, and I try to integrate it into how I approach the field.

At the same time, I've always believed that science, art and mystery are not only highly compatible (in this and any field) but are actually three parts of one whole. What I know, and what I've yet to know that I know, flow together indistinguishably and create my unique approach to clients and clinical situations -- the art. Heck, they create me. And while I adore what science can add to that picture, there isn't an argument in the universe that will convince me that science is any more important than mystery, intuition and subjectivity. We're talking about the mind, about emotions, about self-hood. If it isn't subjective, we are, by definition, off track. How could we possibly quantify why certain people are healing to be around?

One well-recognized marker of mental health is flexible thinking. Practitioners spend a lot of time fostering in our clients a balance of healthy empiricism and risk-tolerant acceptance of the unknown. If the field of psychology doesn't admit pretty soon that the dynamics of pscyhological healing are at least somewhat unquantifiable -- while also unmistakable -- are we then practicing what we preach?

Labels:

Carl Rogers,

Jay Efran,

Laurie Abraham,

new york times,

objectivity,

psychology,

science,

subjectivity

Saturday, August 11, 2007

It's All Over but the Clean-up

Well, friends and Romans, the seven-week journey of my summer job is nearing landfall. It’s all over but the clean-up. (That happens on Monday.)

We started with a full week of training, and then spent six weeks teaching theater games and making films with kids with Asperger’s Syndrome. This is an approach to teaching them social skills – the key deficit for people with Asperger’s, the one that all of them have in common to one degree or another. And an amazingly effective apporach it is, based on the gains I saw during the summer.

They know they’re there to learn social skills (and most, though not all, know that they have Asperger’s). But that’s essentially forgotten, and pretty quickly. The games are fun, and there are dozens of them, so each camper has at least two favorites. We played many of them each day. They get to be hams, to have their intelligence challenged, and to use their imagination nearly all day. In the moment, there’s no awareness going to “Hey! I just made sustained eye contact!” or, “Hey! I just conveyed real feeling with a loud tone of voice!” Or moved their bodies in coordinated ways. Or employed rapid, flexible thinking.

All these apparently small achievements are monumental for Aspies.

After they’ve played the games 20 times, it begins to sink in unconsciously that they are capable of initiating a full connection with another person (or entering a new environment, or doing all sorts of things that previously frightened them) and that good things will usually result. How wonderful is that?

There are many social pragmatics programs out there, and from their popularity, I’m inferring that they must be at least somewhat effective. But from what I’ve read (and heard from satisfied parents on the last day of camp), none of them pack that vital X-factor the theater games do: The gains in social skills come directly from the goals of the activity itself, which just happens to look like a fun game – not a “program” or a “lesson.”

Yet there are dozens of games (and more being created all the time, all over the world), and each targets a different set of social skills. So, they can be craftily combined to target specific kids, or to achieve carefully chosen group goals.

As you can tell, I’m fairly excited about the gains I saw kids make in six short weeks.

And it was both exciting and heartbreaking to see our teens – both the macho, crass, aggressive ones and the awkward, sweet, retiring ones – run up to us and give us hugs and good wishes and good-bye cards. We all milled around at the end of the day; no one wanted to say good-bye. When that last kid (who happened to be one of my favorites) got in his bus, we counselors looked around balefully, shrugged our shoulders and silently headed for the rooms to clean up.

(Of course, there was a wrap-up party last night, and it was boisterous -- a great way to blow off all that pent-up poignancy.)

It was a grueling summer session, five hours of intense contact a day with kids who often can barely stand 10 minutes of such (not to mention the hours of paperwork every day). But I wouldn’t trade the experience for anything. We made a difference in their lives – and they sure affected me pretty deeply. My favorites will be on my mind for weeks, I’m sure.

We started with a full week of training, and then spent six weeks teaching theater games and making films with kids with Asperger’s Syndrome. This is an approach to teaching them social skills – the key deficit for people with Asperger’s, the one that all of them have in common to one degree or another. And an amazingly effective apporach it is, based on the gains I saw during the summer.

They know they’re there to learn social skills (and most, though not all, know that they have Asperger’s). But that’s essentially forgotten, and pretty quickly. The games are fun, and there are dozens of them, so each camper has at least two favorites. We played many of them each day. They get to be hams, to have their intelligence challenged, and to use their imagination nearly all day. In the moment, there’s no awareness going to “Hey! I just made sustained eye contact!” or, “Hey! I just conveyed real feeling with a loud tone of voice!” Or moved their bodies in coordinated ways. Or employed rapid, flexible thinking.

All these apparently small achievements are monumental for Aspies.

After they’ve played the games 20 times, it begins to sink in unconsciously that they are capable of initiating a full connection with another person (or entering a new environment, or doing all sorts of things that previously frightened them) and that good things will usually result. How wonderful is that?

There are many social pragmatics programs out there, and from their popularity, I’m inferring that they must be at least somewhat effective. But from what I’ve read (and heard from satisfied parents on the last day of camp), none of them pack that vital X-factor the theater games do: The gains in social skills come directly from the goals of the activity itself, which just happens to look like a fun game – not a “program” or a “lesson.”

Yet there are dozens of games (and more being created all the time, all over the world), and each targets a different set of social skills. So, they can be craftily combined to target specific kids, or to achieve carefully chosen group goals.

As you can tell, I’m fairly excited about the gains I saw kids make in six short weeks.

And it was both exciting and heartbreaking to see our teens – both the macho, crass, aggressive ones and the awkward, sweet, retiring ones – run up to us and give us hugs and good wishes and good-bye cards. We all milled around at the end of the day; no one wanted to say good-bye. When that last kid (who happened to be one of my favorites) got in his bus, we counselors looked around balefully, shrugged our shoulders and silently headed for the rooms to clean up.

(Of course, there was a wrap-up party last night, and it was boisterous -- a great way to blow off all that pent-up poignancy.)

It was a grueling summer session, five hours of intense contact a day with kids who often can barely stand 10 minutes of such (not to mention the hours of paperwork every day). But I wouldn’t trade the experience for anything. We made a difference in their lives – and they sure affected me pretty deeply. My favorites will be on my mind for weeks, I’m sure.

Sunday, August 5, 2007

Autistic Girls Essentially Different from Autistic Boys?

If you've been enjoying my many earlier posts on my work this summer with teens with Asperger's disorder, I have a nice link for you. The New York Times Sunday Magazine has an interesting article on the gender differences within autism, focusing especially on Asperger's patients.

Now, it's been a mother of a week, and I'm supposed to be resting today, so I'm not going to launch into one of my usual psychology screeds right now. I need to get outside and enjoy the gorgeous summer day, and try to do as little as possible today.

I'll just say that the piece appears basically well-balanced. There are exceptions; in the seven weeks I've been working directly with kids with Asperger's, I've seen various examples that contradict some of the generalizations the author makes about boys or girls with the disorder. But even she admits that the field is still making up its mind about the larger facts on gender differences. Those points she does state firmly seem reasonably well substantiated. Moreover, the questions she raises are quite interesting and have important implications.

Enjoy!

Now, it's been a mother of a week, and I'm supposed to be resting today, so I'm not going to launch into one of my usual psychology screeds right now. I need to get outside and enjoy the gorgeous summer day, and try to do as little as possible today.

I'll just say that the piece appears basically well-balanced. There are exceptions; in the seven weeks I've been working directly with kids with Asperger's, I've seen various examples that contradict some of the generalizations the author makes about boys or girls with the disorder. But even she admits that the field is still making up its mind about the larger facts on gender differences. Those points she does state firmly seem reasonably well substantiated. Moreover, the questions she raises are quite interesting and have important implications.

Enjoy!

Thursday, August 2, 2007

Freud Pumps His Fist

I'm a bit foggy tonight after nearly finishing the fifth of six weeks straight with my campers with Asperger's. (Today was a most victorious day, by the way.) And I'm up extra-early tomorrow in order to be able to take them on their weekly field trip. So tonight, a quick link to a really interesting article in the Times claiming that the unconscious drives our daily actions far more than we think. A tip of the Thinkulous hat to Goat Rope blogger El Cabrero for hipping me to this article.

I can just see old Freud coolly releasing a cloud of cigar smoke, and saying, "Well, duh!" (A rough translation from the German.)

Herr Sigmund may have named the concept over a century ago, but it's only recently that science, that stodgy older sibling, is grudgingly admitting that psychology was right all along. Some key 'graphs:

I can just see old Freud coolly releasing a cloud of cigar smoke, and saying, "Well, duh!" (A rough translation from the German.)

Herr Sigmund may have named the concept over a century ago, but it's only recently that science, that stodgy older sibling, is grudgingly admitting that psychology was right all along. Some key 'graphs:

On the way to the laboratory, [participants in a recent study] had bumped into a laboratory assistant, who was holding textbooks, a clipboard, papers and a cup of hot or iced coffee — and asked for a hand with the cup.Like a lot of academic psychology, the implications of the new research are far more interesting than they are practical. That doesn't stop me from gobbling them up...

That was all it took: The students who held a cup of iced coffee rated a hypothetical person they later read about as being much colder, less social and more selfish than did their fellow students, who had momentarily held a cup of hot java.

Findings like this one, as improbable as they seem, have poured forth in psychological research over the last few years. New studies have found that people tidy up more thoroughly when there’s a faint tang of cleaning liquid in the air; they become more competitive if there’s a briefcase in sight, or more cooperative if they glimpse words like “dependable” and “support” — all without being aware of the change, or what prompted it.

Wednesday, August 1, 2007

Horseplay and Sensory Integration

The boys in my group of Asperger's campers wrestle with each other quite a lot.

We allow a little horseplay in our room, under well-defined parameters. We basically have to. These are 16- and 17-year-old boys, most of whom have ADHD along with their Asperger's. If they sit mostly still during games and meetings, we let them grapple a little during the less structured times, as long as they keep their distance from others, and keep it reasonably safe.

However, there's another piece to it beyond, "boys with ADHD will be boys, times two." Many Aspies have sensory integration issues, and they are often almost literally "going out of their skin." If you've heard of Temple Grandin's discovery that certain animals and autistic people both calm down when they feel pressure against their bodies, you have a very general idea of what this means.

In moments of sensory overwhelm younger Aspies might flop on the floor and pile bean bags over their own bodies. If they're 16 or 17, and too "cool" to do that, they'll wrestle. (Some have other self-soothing mechanisms, but space doesn't permit me to detail those here.) It does get annoying, because some of them cannot sit still for more than 15 or 20 seconds at a time. While others are trying to have a quiet meeting, or do acting games, they'll be twisting each others' wrists, fingers, elbows, and so on. It looks a lot like the old "boys will be boys" behavior, but underneath, there's more going on.

We try to walk the line between letting them self-soothe and keeping the group attentive and cohesive. It gets very, very tiresome sometimes. But if I ever doubt their genuine need for it, I just look at the happy smile of one particular camper who is perpetually trapped in a head-lock or full-nelson, pretty much all day. He complains the whole time, but without it, I think he would actually drive himself, and us, even more crazy.

We allow a little horseplay in our room, under well-defined parameters. We basically have to. These are 16- and 17-year-old boys, most of whom have ADHD along with their Asperger's. If they sit mostly still during games and meetings, we let them grapple a little during the less structured times, as long as they keep their distance from others, and keep it reasonably safe.

However, there's another piece to it beyond, "boys with ADHD will be boys, times two." Many Aspies have sensory integration issues, and they are often almost literally "going out of their skin." If you've heard of Temple Grandin's discovery that certain animals and autistic people both calm down when they feel pressure against their bodies, you have a very general idea of what this means.

In moments of sensory overwhelm younger Aspies might flop on the floor and pile bean bags over their own bodies. If they're 16 or 17, and too "cool" to do that, they'll wrestle. (Some have other self-soothing mechanisms, but space doesn't permit me to detail those here.) It does get annoying, because some of them cannot sit still for more than 15 or 20 seconds at a time. While others are trying to have a quiet meeting, or do acting games, they'll be twisting each others' wrists, fingers, elbows, and so on. It looks a lot like the old "boys will be boys" behavior, but underneath, there's more going on.

We try to walk the line between letting them self-soothe and keeping the group attentive and cohesive. It gets very, very tiresome sometimes. But if I ever doubt their genuine need for it, I just look at the happy smile of one particular camper who is perpetually trapped in a head-lock or full-nelson, pretty much all day. He complains the whole time, but without it, I think he would actually drive himself, and us, even more crazy.

Sunday, July 29, 2007

The Dangerous Book for Boys

[Reminder: Help out Thinkulous by taking the Reader Survey, at top right of the page!]

This week my extremely thoughtful betrothed bought a present for me. I've been working like a dog both on and off the job, and she wanted to lift my spirits a bit. She also knows I am very friendly to the psychological school that says that boys are currently having the "boy" squeezed out of them left and right. (I've recommended Michael Thompson's excellent documentary, Raising Cain, before, and I'm doing so again).

With all those thoughts in mind, she went out and got me The Dangerous Book for Boys, by Conn and Hal Iggulden, a couple of Brits who were tired of the "sit still in your seat and, by the way, no recess for you" trend. They teach a wide range of boy-oriented skills, tricks and history, most of which has been left by the wayside years ago.

I'm of two minds about the book. Most of me loves it. It's definitely a fun read. I'm already practicing some sleight of hand coin tricks, and planning to build a battery out of quarters and vinegar-soaked paper on the next rainy Sunday afternoon.

On the other hand, it's also strongly biased towards the scientific and physical-toughness aspects of masculinity and away from the artistic. Sadly, the book is also a little bit sexist. It would have been better not to mention girls at all than to have the one entry on them, out of dozens, consist of a bunch of flirting tips like "give them flowers" and "listen to them." Useful thoughts -- but highly limiting. If the Igguldens had simply focused on boys and not opened this can of worms, I could more easily celebrate their biased approach. It doesn't bother me in the least that the book is directed only at boys; it pleases me. My fiancée clearly wasn't offended, either.

For better and for worse -- and it's both -- the book could have been published in 1965. Which is one reason it may be read more by guys my age than by our sons. (With that said, when I have one, I will give him this book -- along with a bunch of reading that delights in the softer side of life).

I do fondly remember my days launching model rockets and shooting corks out of bottles filled with baking soda and vinegar. The Igguldens cover similar fun and bracing territory, such as:

- - How to build an electromagnet

- Well written short bios of explorers and inventors like Robert Scott and the Wright Brothers

- Writing in invisible ink

- Dozens of fun Latin phrases and their translations

- The U.S. naval flag code

I'm working my way through, dreamily remembering the days I spent poring over similar compendia lo, those many years ago -- and how I used those manuals to memorize cool facts, build things, and blow up stuff.

Saturday, July 28, 2007

A Real Psychological Thriller

First, if you haven't participated yet in the Thinkulous reader survey, please consider it. It helps me a lot, and it takes two minutes (really -- I have the stats to prove it!). The link is at the top right.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Just finished a fun 1970s addition to the Sherlock Holmes lore: The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, by Nicholas Meyer.

The story takes place well after the era of the last episodes by the great Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Watson is happily married and has been prevented from adventuring with his old friend Holmes by his growing private practice and new home life. He hasn't seen him in some time. One night, however, he finds out that the world's greatest detective has descended into a terrible state, including a raging addiction to cocaine (which was legal in England in Victorian times).

It seems there are precedents in Conan Doyle's work -- stories in which Holmes dabbled in the drug even while in his prime. But now, it's got him in its demon claws, and he's descended into near-madness. In desperation, Watson turns to the one man in all Europe who might be able to help: A young firebrand doctor in Vienna who's been doing work with cocaine; a fellow named Sigmund Freud.

Oh, joy! Two of my favorite subjects -- detective stories and psychology -- in one book! The prose is fairly enjoyable, though a bit purple at times, especially considering Meyer's ill-advised conceit that the story was actually written by Watson (née Conan Doyle). Meyer also messes around a bit with the masterfully established Sherlockian back-story, and it often rings a bit tinny. There are a few wince-able moments, but generally, it's very fun summer reading. It was delightful to make Freud's acquaintance in this much more accessible (albeit highly apocryphal) manner for a few action-packed days. There are lots of lovingly detailed scenes of old London and Vienna, and a climactic railroad chase that makes today's Hollywood car chases pale terribly by comparison.

A passage towards the end nicely sketches the connection between two of my favorite subjects. Watson addresses Freud with awed respect, after the latter uncorks one of the more towering of the revisionist theories Meyer plants in the book (which I won't spoil here):

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Just finished a fun 1970s addition to the Sherlock Holmes lore: The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, by Nicholas Meyer.

The story takes place well after the era of the last episodes by the great Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Watson is happily married and has been prevented from adventuring with his old friend Holmes by his growing private practice and new home life. He hasn't seen him in some time. One night, however, he finds out that the world's greatest detective has descended into a terrible state, including a raging addiction to cocaine (which was legal in England in Victorian times).

It seems there are precedents in Conan Doyle's work -- stories in which Holmes dabbled in the drug even while in his prime. But now, it's got him in its demon claws, and he's descended into near-madness. In desperation, Watson turns to the one man in all Europe who might be able to help: A young firebrand doctor in Vienna who's been doing work with cocaine; a fellow named Sigmund Freud.

Oh, joy! Two of my favorite subjects -- detective stories and psychology -- in one book! The prose is fairly enjoyable, though a bit purple at times, especially considering Meyer's ill-advised conceit that the story was actually written by Watson (née Conan Doyle). Meyer also messes around a bit with the masterfully established Sherlockian back-story, and it often rings a bit tinny. There are a few wince-able moments, but generally, it's very fun summer reading. It was delightful to make Freud's acquaintance in this much more accessible (albeit highly apocryphal) manner for a few action-packed days. There are lots of lovingly detailed scenes of old London and Vienna, and a climactic railroad chase that makes today's Hollywood car chases pale terribly by comparison.

A passage towards the end nicely sketches the connection between two of my favorite subjects. Watson addresses Freud with awed respect, after the latter uncorks one of the more towering of the revisionist theories Meyer plants in the book (which I won't spoil here):

"You are the greatest detective of all." I could think of nothing else to say.It's fun to watch these two legends, however fictionalized, try to impress each other with their well-matched mastery of, and all-consuming passion for, their fields. In novels, at least, those fields don't difffer all that much.

"I am not a detective." Freud shook his head, smiling his sad, wise smile. "I am a physician whose province is the troubled mind." It occured to me that the difference was not great.

Thursday, July 26, 2007

Albert Ellis: Great and Controversial

[Ed. note: It's survey week! Have you helped out Thinkulous by taking the poll, top right side of the page?]

The great Albert Ellis died on Tuesday. He made a huge contribution to the field of psyhology -- and outraged professionals and lay-people around the world.

He was one of the founders of what eventually became cognitive behavioral therapy. He believed our past is important, but doesn't affect us as much as we affect ourselves through our unconscious thought patterns.

The Boston Herald (which I usually avoid) ran a pretty good summary of his life here.

During my year-long Theories of Psychology course at grad school, we watched a film in which one (brave) woman underwent one session each with three giants of the field: Carl Rogers, Fritz Perls, and Ellis. My classmates were utterly turned off by Ellis' blunt, no-nonsense style, and the professor did a lot of eye-rolling and winking. I was the only one who said, "I don't think I'd want to work with this guy long-term, but if I could get six sessions with him, I bet I would be a happier man."

I'm definitely not a pure CBT therapist (too many great approaches out there to lean on just one), and Ellis' personal style is not for most people. But the field is tremendously more effective because of his work. And hey, Ellis was a "Take Me or Leave Me" kind of guy, and frankly, that's kind of refreshing in a psychotherapist -- or anyone.

The great Albert Ellis died on Tuesday. He made a huge contribution to the field of psyhology -- and outraged professionals and lay-people around the world.

He was one of the founders of what eventually became cognitive behavioral therapy. He believed our past is important, but doesn't affect us as much as we affect ourselves through our unconscious thought patterns.

The Boston Herald (which I usually avoid) ran a pretty good summary of his life here.

During my year-long Theories of Psychology course at grad school, we watched a film in which one (brave) woman underwent one session each with three giants of the field: Carl Rogers, Fritz Perls, and Ellis. My classmates were utterly turned off by Ellis' blunt, no-nonsense style, and the professor did a lot of eye-rolling and winking. I was the only one who said, "I don't think I'd want to work with this guy long-term, but if I could get six sessions with him, I bet I would be a happier man."

I'm definitely not a pure CBT therapist (too many great approaches out there to lean on just one), and Ellis' personal style is not for most people. But the field is tremendously more effective because of his work. And hey, Ellis was a "Take Me or Leave Me" kind of guy, and frankly, that's kind of refreshing in a psychotherapist -- or anyone.

Wednesday, July 25, 2007

Theory of Mind

First things first: It's still survey week at Thinkulous. I'd love it if you helped me out by taking the survey via the link at the top-right-hand side of this page.

Interesting post recently on Mind Hacks, one of my favorite blogs (part of me is a huge psych geek). Since I've been writing about this recently, I thought I'd post an excerpt that explains theory of mind rather well in a brief way:

Interesting post recently on Mind Hacks, one of my favorite blogs (part of me is a huge psych geek). Since I've been writing about this recently, I thought I'd post an excerpt that explains theory of mind rather well in a brief way:

People with autism or related conditions are often poor at both deception and recognising deception in others. It's not always the case, but it's quite a common attribute.I recommend the post and much of the site to those who like to explore why and how we think and feel what we do.

Baron-Cohen's article explores what we know about some of the differences in autistic thinking, and what might be so different that an effective understanding of deception becomes almost impossible.

He argues that a key skill is 'meta-representation', the ability to think about other thoughts, imaginary scenarios or abstract principles in yourself or others.

The key is that it's not just thinking or imagining, it's being able to think about thinking or imagining.

When this specifically involves thinking about what other people are thinking, understanding their perspective, it is often called 'theory of mind'.

You can see why this is a key skill in deception. You need to have a theory or understanding of what the other person is thinking or is likely to think, to work out how to hide the real state of the world from them.

Labels:

Asperger's Syndrome,

autism,

psychology,

theory of mind

Monday, July 23, 2007

Reader's Survey

It's time for FOSIRS!

That's the First Occasional Statistically Insignificant Reader Survey.

If you have visited Thinkulous more than once or twice, I would really appreciate it if you took part. I could really use your perspective as I ponder the direction of this blog.

It takes less than two minutes. Your contact info is not collected, and all answers are completely anonymous.

Click Here to take survey

That's the First Occasional Statistically Insignificant Reader Survey.

If you have visited Thinkulous more than once or twice, I would really appreciate it if you took part. I could really use your perspective as I ponder the direction of this blog.

It takes less than two minutes. Your contact info is not collected, and all answers are completely anonymous.

Click Here to take survey

Saturday, July 21, 2007

Boys' Psychology and Asperger's, Pt. II

Yesterday's post outlined the general ways that Asperger's and boy-code behavior. We also met camper Will, a sensitive, highly literal-minded Aspie who, by dint of his defecits, gets hit even harder by the boy code than most.

(To reiterate: All persons are fictional composites here.)

Envision now a highly boisterous game of keep-away, involving seven campers and three counselors. Will – a good athlete – is in the middle, and, at a blatantly easy opportunity, fails to gain the ball.

Now, Camper Evan is in high spirits (the more so because he is one of the boys exchanges teasing quite good-naturedly, and there’s a lot of that going on with his friends at the moment) and he quickly calls out in a playful way, “You suck, Will!” Things are happening fast in this moment, and, though he’s quick physically, processing delays prevent Will from making any interpretations to counteract his natural literal interpretation (though he’s quite intelligent).

In other words, Will simply knows that, “Evan just told everyone very loudly that I suck.” And that’s all he knows.

Confusion and shame almost instantly slam Will like a big ocean wave, followed quickly (faster than his delayed thoughts can mediate) by anger and fear. I think you have the general idea of what follows; space doesn't allow for details.

I want to reinforce here that what Asperger's kids go through socially often varies only in degree from what neurotypical kids go through. I can admit that I had many moments like the one above while growing up. However, Aspies go through more extreme versions of social distress because their unique characteristics make them more apt to experience social awkwardness or cruelty. The situations and attendent emotions might feel familiar, but don't let that fool you. Aspies are different.

I’ve probably raised more questions with these posts than I’ve answered. I would have to write a bona fide academic paper to thoroughly address all the issues. I mainly wanted to describe how interesting it is that the code of neurotypical boys comes into play so directly with our campers, too – yet with a twist that can make it all the more confusing and damaging.

(To reiterate: All persons are fictional composites here.)

Envision now a highly boisterous game of keep-away, involving seven campers and three counselors. Will – a good athlete – is in the middle, and, at a blatantly easy opportunity, fails to gain the ball.

Now, Camper Evan is in high spirits (the more so because he is one of the boys exchanges teasing quite good-naturedly, and there’s a lot of that going on with his friends at the moment) and he quickly calls out in a playful way, “You suck, Will!” Things are happening fast in this moment, and, though he’s quick physically, processing delays prevent Will from making any interpretations to counteract his natural literal interpretation (though he’s quite intelligent).

In other words, Will simply knows that, “Evan just told everyone very loudly that I suck.” And that’s all he knows.

Confusion and shame almost instantly slam Will like a big ocean wave, followed quickly (faster than his delayed thoughts can mediate) by anger and fear. I think you have the general idea of what follows; space doesn't allow for details.

I want to reinforce here that what Asperger's kids go through socially often varies only in degree from what neurotypical kids go through. I can admit that I had many moments like the one above while growing up. However, Aspies go through more extreme versions of social distress because their unique characteristics make them more apt to experience social awkwardness or cruelty. The situations and attendent emotions might feel familiar, but don't let that fool you. Aspies are different.

I’ve probably raised more questions with these posts than I’ve answered. I would have to write a bona fide academic paper to thoroughly address all the issues. I mainly wanted to describe how interesting it is that the code of neurotypical boys comes into play so directly with our campers, too – yet with a twist that can make it all the more confusing and damaging.

Boy's Psychology Applies, Regardless of Asperger's

(All names in this post are fictional, and all case examples are composites.)

I’m working this summer at a camp that has found a very fun way to teach social pragmatics to kids who have Asperger’s Syndrome (go here for all related posts). Yesterday marked three weeks in – the half-way point. The group seems to have taken a step forward this week, as various individuals come out of their shells and get more comfortable.

Others, in my group and elsewhere, are still suffering. Some of that derives from their inability to understand typical boy’s behavior. One of the deficits that defines the disorder is an extreme literalism in all interactions. When this literal quality runs up against the kind of teasing and rough-housing to which boys have subjected each other from time immemorial, you can imagine the results. Even high-school-age boys end up deeply wounded and permanently on the outside of social acceptance.

(I focus here on boys because I’m very intrigued by boys’ psychology, and because boys are the overwhelming majority in the Asperger’s population, and thus at our camp. We have one girl in our group of nine campers, and some groups are all boys.)

I’ve said elsewhere (and it has been seconded in learned comments on one of my Asperger's-related posts) that just because someone has Asperger’s doesn’t mean he doesn’t have a personality separate from the disorder. Our teenage boys curse, wrestle, and insult each other in every offensive flavor their considerable creativity and intelligence can generate. American boys (as a vast but viable generalization) have always found it easier to connect with each other in this manner than to express direct, non-ironic affection for each other. Call it sad, call it fun. Call it all-American, or call it oppressive cultural gender role influence. Call it what you will, but it is real and prevalent. And many Aspies end up on the painful end of the exchange, because they simply can not get it.

About this literalism: Let’s say camper Will asks me when we’ll be going outside, and I casually reply, “In half an hour.” If 31 minutes go by, Will immediately, loudly protests my violation of my word. There are other Asperger characteristics at play in that interaction (inflexible thinking, rule-bound behavior), but literalism is a big one.

Keep in mind also that Will has entered our highly rambunctious camp group after 10 or so years of relentless teasing of a much more vicious sort, at the hands of truly mean boys at school. They find his other Asperger traits (a speech defect, or obsession with favorite topics, or slow mental processing time) easy fodder – and then zero in all the more cruelly when they find out Will can quite easily be deeply wounded. By the time he arrives at camp, he often takes any comment as a sword through the heart, much less one that – heard literally – contains clearly negative language directed at him.

Tune in tomorrow to find out what happens when Will’s literalism runs up against boy-code behavior.

I’m working this summer at a camp that has found a very fun way to teach social pragmatics to kids who have Asperger’s Syndrome (go here for all related posts). Yesterday marked three weeks in – the half-way point. The group seems to have taken a step forward this week, as various individuals come out of their shells and get more comfortable.

Others, in my group and elsewhere, are still suffering. Some of that derives from their inability to understand typical boy’s behavior. One of the deficits that defines the disorder is an extreme literalism in all interactions. When this literal quality runs up against the kind of teasing and rough-housing to which boys have subjected each other from time immemorial, you can imagine the results. Even high-school-age boys end up deeply wounded and permanently on the outside of social acceptance.

(I focus here on boys because I’m very intrigued by boys’ psychology, and because boys are the overwhelming majority in the Asperger’s population, and thus at our camp. We have one girl in our group of nine campers, and some groups are all boys.)

I’ve said elsewhere (and it has been seconded in learned comments on one of my Asperger's-related posts) that just because someone has Asperger’s doesn’t mean he doesn’t have a personality separate from the disorder. Our teenage boys curse, wrestle, and insult each other in every offensive flavor their considerable creativity and intelligence can generate. American boys (as a vast but viable generalization) have always found it easier to connect with each other in this manner than to express direct, non-ironic affection for each other. Call it sad, call it fun. Call it all-American, or call it oppressive cultural gender role influence. Call it what you will, but it is real and prevalent. And many Aspies end up on the painful end of the exchange, because they simply can not get it.

About this literalism: Let’s say camper Will asks me when we’ll be going outside, and I casually reply, “In half an hour.” If 31 minutes go by, Will immediately, loudly protests my violation of my word. There are other Asperger characteristics at play in that interaction (inflexible thinking, rule-bound behavior), but literalism is a big one.

Keep in mind also that Will has entered our highly rambunctious camp group after 10 or so years of relentless teasing of a much more vicious sort, at the hands of truly mean boys at school. They find his other Asperger traits (a speech defect, or obsession with favorite topics, or slow mental processing time) easy fodder – and then zero in all the more cruelly when they find out Will can quite easily be deeply wounded. By the time he arrives at camp, he often takes any comment as a sword through the heart, much less one that – heard literally – contains clearly negative language directed at him.

Tune in tomorrow to find out what happens when Will’s literalism runs up against boy-code behavior.

Thursday, July 19, 2007

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

The Tao of Therapy

Things are progressing well at the camp I work at for kids with Asperger's Syndrome. (See previous posts, and this one will make more sense.) Once again, I've learned that the relationship can do most of the work of healing.

Many years ago, Carl Rogers astutely and repeatedly insisted that people basically will heal themselves when they are in the context of a healthy therapeutic relationship. Subsequent research has strongly supported this; the school of therapy used affects the outcome far less than the qualities of the professional in the relationship (as perceived by the client).